Pulling No Punches: Anthony Joshua the new breed in a new era for the heavyweight division but can he have the Muhammad Ali Effect ?

Anthony Joshua, they say, is many things. He is the biggest star in British boxing; he is the owner of the International Boxing Federation (IBF) world heavyweight title. He is also unbeaten, and on the cusp of fighting Wladimir Klitschko, the huge Ukrainian who dominated the heavyweight division for almost a decade. Timing is everything in sport, and Joshua has the moment to show that the torch is changing hands on April 29 at a sold-out Wembley Stadium.

This is a legacy moment. A takeover moment for the beginning of ‘The Joshua Era’ just as there was a Mike Tyson era, a Muhammad Ali era, a time of Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. The heavyweight champs who shifted the dial. Inside and outside their sports, because they had something special. Anthony Joshuas has those qualities.

But this is a very risky, 50/50 fight. Defeat Klitschko and Joshua will rise from an emerging young star, to the biggest star in world boxing, and arguably the biggest star in British sport. Win another six or seven fights, wipe out his rivals, and Joshua becomes a global sports star. A perfect resume for the next five years and he could become the first billionaire boxer. It’s plausible. But they say ‘expect the unexpected’ in boxing, and just one punch can imperfect the best-laid plans.

In 2012 he won a gold medal at the London Olympics, and four years later he defeated Charles Martin to claim his first world title as a professional boxer. In that time he became known as AJ; a brand, a money-making juggernaut, a commodity whose earning potential stretches far beyond what can be achieved in the four corners of a boxing ring.

Boxing fans now turn up in droves to watch him fight. Five times he has sold out London’s 16,000-capacity O2 Arena, while, on April 29, some 90,000 spectators, a post-war record, will descend on Wembley Stadium in the hope of seeing Joshua dispatch Wladimir Klitschko with the same kind of violence and ease he has exhibited in downing his 18 other opponents. Those at home, meanwhile, the ones not lucky enough to snare a golden ticket, will pay £16.95 for the chance to watch Joshua in action, just as they have done for his previous four bouts.

All this goes to show is that AJ has sussed the game. He’s playing with house money. He is thriving in a sport that so often chews up and spits out its players, leaving them with nothing. Consequently, Joshua, at 27, is a rich man, a successful man, a popular man, and he has so far, unlike Tyson Fury, done everything right during his brief tenure as champion.

[His promoter Eddie Hearn describes him as “a bad guy trying to be good. And he needs to be a bad boy to fulfill his dreams in the ring’.]

“Have we seen anything like Anthony Joshua before?” says Hearn, a man who has promoted Joshua since the advent of his professional career in 2013. “This is a guy who transcends the sport. This is a guy who has already hit phenomenal figures, whether at the gate or on Sky Box Office. He’s a phenomenon.”

“There are not many stars in boxing nowadays. You’ve got some outstanding fighters, but AJ is a star. The fact he is a heavyweight obviously helps. I think everyone is pinning their hopes on him. He is the guy to take boxing and the heavyweight division to new levels. I think he has the crossover appeal to do it.”

Joshua knows all this, of course. He’s surrounded by people who, on a daily basis, remind him of how great he is and how great he can be and how much money can be generated in the process. All part and parcel of being heavyweight champion of the world, I suppose. The momentum. The excitement. The building towards something memorable. But the key to Joshua’s success lies in his ability to take this giddy enthusiasm and brush it off with a roll of the eyes, a shrug of broad shoulders or a Brunoesque chuckle.

He takes little seriously; not his own supposed greatness, not his air of invincibility, not even the thought of preserving his undefeated record. Instead, Joshua speaks openly of his fragility and flaws. He knows failure is around the corner – maybe not now, maybe not tomorrow, but at some point the two shall meet. He is, it would seem, blessed with an ability to stay grounded at a time when everyone else in his vicinity is floating, reaching for the stars.

The truth is, Joshua couldn’t care less about money and fame. All he cares about is winning. Crucial to his success, though, Joshua is a marketing man’s dream, which is to say he looks the part – all jutting abdomen and bulging biceps – and, more importantly, says all the right things at the right time. It’s why he is, according to his promoter, Eddie Hearn, the most bankable commodity in the world of boxing right now.

It’s why a country unnerved in 2015 by the emergence of Tyson Fury, controversial, unpredictable and God-fearing, have fully embraced Joshua, ostensibly his replacement, and the relative simplicity he brings.

In a post-Tyson Fury world, some have gone as far as to say Anthony Joshua is the heavyweight champion Great Britain not only wants but needs. He is the man to repair the damage, the man to clean up the mess, the man to represent his nation the right way. Our apology to the world. The man to restore dignity to the sport’s blue riband title, once owned by Muhammad Ali, Smoking’ Joe Frazier, and George Foreman.

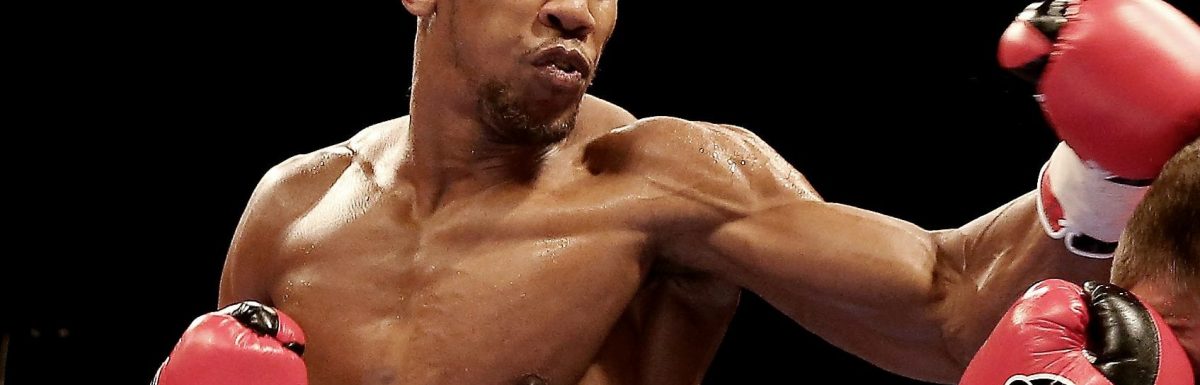

As per the truncated synopsis his publicists might send to potential sponsors, Anthony Joshua is a 27-year-old boxer, athlete and role model from Watford, north London. He’s six-foot-six inches in height, weighs just shy of 18-stone and has a reach of 82-inches. He has a 54 inch chest. HIs fist, clenched, measures 14 inches. He is built like an England No 8, an gridiron linebacker or an NBA power forward. Or to most women and young men who aspire to be like him, a Greek God, or the proverbial barn door.

The force of being punched by Joshua’s right hand is like being hit by a 4kg sledgehammer at 30 miles per hour. His left hand jab takes just a few hundredths of a second to travel from his chin to extend his opponents face.

Hearn had met Joshua for the first time at the English Institute of Sport. Well, heard him, in fact, when the huge heavyweight was training with the GB squad ahead of the Games. “ I was up there with another boxer I was promoting, here was this noise, and I’ll never forget it. I turned around and it was the heavy bag being almost taken off its hinges by Joshua. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

There is an expression for his routine: “Embracing the grind.” Monday to Friday, training absorbs his entire life. Joshua eats six times a day during training and as many as 3500 calories. Sleep comes early. Joshua has a fighting spirit, the DNA of an elite athlete, but the third element is his drive. in and out of the sport, he pushes himself.

His mum, Yeta Odusanya, a Nigerian immigrant – and a social worker keeps him in check. She also still does his washing. Some things won’t change for Joshua; this routine, his friends, his goals. When back in London, when not training in Sheffield, he sees no issue staying in the ex-council flat in Temple Fortune with his mother.

“It just seems very normal to him,” says Freddie Cunningham, Joshua’s manager. “We’ll turn up to go to some £100,000 global photoshoot for a huge brand, and then the GQ Sportsman of the Year awards, and we’ll have a cup of tea with his mum and play with their little dog Roxy while he’s getting his stuff together. We’ll come back after a 12-hour day and we’re both absolutely knackered and she’ll ask if he’s had a good day and ask what he got up to. He’ll say I just had a photoshoot or won an award. It’s very funny. He’ll then put the award up on his mantelpiece and his mum will look at it. He keeps the home life very calm and detached from everything else. He’s a normal guy in his area. He goes to the launderette, the post office. At home he wants to keep that. He doesn’t want to change.”

AJ is the image they try to push, the one they, those around him, have cultivated since he became the nation’s golden boy in 2012. But, in truth, Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua has more in common with Tyson Fury than just a belt and an unblemished record.

Joshua, too, has his rough edges, his past, his mistakes. To gloss over this would be to do a disservice to the eventual redemption story. Indeed, promoter Hearn has often described the jewel in British boxing’s crown as “bad boy trying to be good”. What he means is Joshua’s affability and jovial nature serves to disguise a darkness he uses to conjure brutal knockouts, a darkness which saw him get mixed up in the wrong crowd as a youth; the dirt on an otherwise pristine athlete.

Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua was born in Watford, the son of Nigerian mum and a Nigerian/Irish father, Robert. Twelve years aho, he was on a fast track to trouble 10 years ago. A huge, rangy teenager, he had fast cars, women and even drugs on his mind. Brushes with the law were frequent between 2006 and 2010.

From 16, there had been trouble. As a footballer, and an athlete who could sprint 100 metres in just over 10 seconds, was playing a game for his school, Langley Secondary, when he grabbed an opponent by the neck and threw him over his shoulder. There was a formal complaint, and Joshua was charged with actual bodily harm for which he received a warning. There were streets fights, too, and on one occasion, he ended up on remand in Reading gaol.

Even when the man-mountain of a boxer was on the cusp of achieving world honours as an amateur, in 2010, he was arrested with cannabis in his car. Police did not have much of an issue identifying him either: Joshua was wearing his Great Britain team boxing tracksuit at the time.

He was charged with possessing cannabis and intent to supply the drug. He pleaded guilty, was suspended from Britain’s boxing squad and sentenced to a 12-month community order and 100 hours’ unpaid work. His past life of “clubbing and girls” had come back to haunt him and some were even predicting the end of a once promising career.

It could have been the end. That it wasn’t speaks to Joshua’s driven mindset and also to the pull and influence of boxing. For if it wasn’t for boxing, this thing Joshua, a late starter, only discovered at the age of eighteen, an isolated incident in an England tracksuit might represent less of a blotch on a copybook and more of a starting point on the road to something destructive.

“Before boxing, I didn’t know what I was doing. Things weren’t going too well,” says Joshua. “I’ve always wanted to be successful but didn’t know what I was going to do. I tried bricklaying. Some of my mates went on courses and set up their own businesses. They’re doing well. I wanted to do something that would allow me to progress and potentially help my family.”

“I’m just trying to do something positive. I’ve got an opportunity now. This wasn’t planned. I didn’t start boxing when I was 10 or 11 years old. I fell into this. At first it was just a bit of fun. I wanted to get strong. I enjoyed it. But now, according to everyone else, I can potentially become the best heavyweight on the planet. That is unbelievable to know I could potentially achieve that.”

It’s all potential with Joshua. Potential this, potential that. It’s part of his charm, the buzzword he consults to ensure he remains rooted. But, no matter how many times it’s repeated – in addition to his ‘stay hungry’ mantra – there remains a maelstrom of hype and forward-planning. That’s the fascinating dichotomy at play. Joshua, the boxer, the star, the cause of the storm, is the one simultaneously hitting the brakes on a hype machine that has already made him a multi-millionaire and secured sponsorship deals with Under Armour and Beats by Dre. He is the CEO of his own company ‘Anthony Joshua’. And with sponsorships, it is bespoke. Less is more.

Boxing promoter Hearn says that he has “never seen women fall at a fighter’s feet” like they do for Joshua. In fact, reveals Hearn, the fighter with the sculpted physique is “actually quite geeky” around women. But Joshua does have a baby son ‘JJ’, though he is not in a relationship with the mother, Nicole Osbourne, 27 [CHECK], a schoolmate from Watford, described as a pole-dsncing teacher by oner tabloid in 2015, and his son as “a secret lovechild” though the boxer has been daring Ms Osbourne on and off since their schooldays.

Right now though, women are not a distraction. “He’s so focused on his boxing,” says one of his team. “I think his lifestyle is quite boring. He’s very regimented. Boxing has given him… he embraces that lifestyle. Boxing gave him direction. It gave him a routine. Now when he’s in camp it’s Monday morning drive to Sheffield, check into the hotel, stay there, work with coach Rob McCracken all week, spar, Friday drive home, get into bed, play some video games, my mates come round, get some food in… he’s quite happy with that.”

Make no mistake, Joshua is the one in control. He’s every bit as controlling in business, in fact, as he is on fight night, when having his way with overmatched opposition. He has his own management company, for example, and there are signs he will one day promote. The AJ brand is big, its reach wide. There are T-shirts and snapbacks and phone cases and shaker cups. His potential – that word again – extends beyond boxing.

His rise is also well-timed. Eddie Hearn, after all, is a promoter who has made boxing ‘sexy’ again – his word, not mine – and heralded a new dawn for the sport in this country. Under his watch it has been repackaged as The Great Night Out; there are recognisable star attractions, a few of which are household names, powered by social media presence and personality; there is high demand for tickets; pay-per-view numbers continue to soar; mainstream sponsors have reignited their interest. The moment to capitalise, therefore, has never been greater.

“In camp AJ watches programmes about Mike Tyson and listens to how he lost his money,” says Cunningham. “He’s very, very aware that he’s in an industry that has no guarantees. It’s not a working career where you can have 40 years or 50 years. He knows it’s 10 years. After those 10 years it could be the ‘David Beckham effect’ where you then go even bigger and become global.”

“But he knows he’s got a certain amount of time, he needs to maximise the money, do what he’s doing and put the foundations down long term. Hopefully when he’s 40 he’s not having to box for money. He’s either boxing because he’s still very good at it and wants to or he can say, ‘No, I’ve got plenty of money and five different businesses set up and all are doing extremely well.’”

Behind the scenes, say his team, Joshua studies. He studied obscure heavyweight boxers from the past; he studies the break-up of Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield’s wealth – both men amassed $300 million dollar fortunes as heavyweight champions of the Eighties and Nineties, but lost most of it. He studies business books; spends hours talking to Barry Hearn, the sports impresario and father of his promoter Eddie, about accounting.

“He reads a lot. I think his heroes change,” says Hearn. “He loves business and he has a lot of respct for people who have done well in business. He likes talking to my dad a lot, deeply, about business and planning and investments and stuff like that. He’s a sponge. He likes to just absorb information. Really diverse information. Sometimes quite strange information. You’ll see him reading a book on accounting or something like that.”

That eclecticism showed in January when he shared a photo of himself praying in a mosque in Dubai. ‘Besides luck, hard work & talent.. Prayer is a solid foundation. It was nice to join my brother as he led through afternoon prayer (asr),’ he tweeted to his 800,000 followers, along with an emoji showing hands clasped in prayer. He also shared the photo to almost 2 million followers on Instagram. A torrent of abuse followed. Some Muslims joined in, asking why he was wearing sunglasses in the mosque and looking upwards instead of at the floor.

He’s clearly authentic, and has a great presence. His smile lights up a room. He spends 90 minutes at public workouts having selfie with fans and signing countless autographs.

Hearn says that the fighter refuses to roll over when discussing his career and moves. “It’s a proper business he’s running and commercially his deals are sensational. There’s never been a boxer on this planet who has commercial deals like Anthony Joshua and that includes Floyd Mayweather, because he didn’t really have any. Manny Pacquiao had some big ones but still not on Joshua’s level.”

Joshua’s opponent, Klitschko, the former world heavyweight champion, is now 41. Hew boxes not for money, he says, but for legacy, for the love of it, for redemption. This fight with Joshua will be his first since he relinquished his vast collection of title belts to another British heavyweight, Tyson Fury, in November 2015. Many believe it might represent his last.

Joshua will overlook nothing. “If I was to get caught up in the hype and start believing I’m better than everyone,” Joshua tells me, “that’s probably when I’d start getting beaten. I think I’m confident in my ability, but not to the point where I start disrespecting my opponents or slacking in the gym.”

“I’ve got the contender’s mentality, not the champion’s mentality. That’s what separates the guys at the top who stay there. They keep that contender’s mentality. Win or lose, I’ll always give 110%. That’s what I’m doing at the moment and it’s working. And nothing is going to change”